Aina Marti-BalcellsHéloïse Press, FOUNDERFor this month’s Featured Press Spotlight we're joined by former lecturer, now pioneering publisher, Aina Marti-Balcells, to find out more about Canterbury’s indie champion of world-wide female narrative and contemporary translated fiction, Héloïse Press.

That was at the end of the longest lockdown, I just realised that although I was working I wasn’t entirely happy. That’s a bit of a cliche but it’s true. I was reading one of the books by Rachel Cusk, Arlington Park… which is very special to me. It’s about five women in their late thirties… I found that these women were at a stage in their lives where they were releasing that they’d all made bad choices at some point. I was at a crossroads with what I was going to do next, I thought, “Well, I still haven’t regretted my choices.” |

JR: I was wondering if you could tell us a little about your time in academia and how you came into the publishing world. It sounds as though you decided that if no one else was doing it, you might as well do it yourself!

AMB: So, I came to this country, I think, about thirteen years ago. I’m from Spain originally and I came to study literature, and that has been my passion forever, ever since I was very young. I came to do my Masters and I loved it and then went into my PhD and I loved it, and then I was a teaching at the uni here in Canterbury for two years.

Now, James, my passion in life was to become an academic and keep studying literature and I don’t know if you know how the landscape is at the moment, but it’s really terrible. They’re cancelling a lot of jobs in the Humanities and many of my lecturers were made redundant. It’s been really tragic. So, anyway, I couldn’t find a permanent position, not here or in any other university in this country for Literature - I did Comparative Literature. I basically focussed on literature in English, French and German. So, that, I think - well, now I’m jumping a little bit - there’s a lot of talk in this country about whether literature in translation is as popular as literature in English. The conclusion is no! For instance, not like it is in France or Spain where people read far more international authors, and I think that translates also in academia. Because, if you’re doing English there are far more jobs for English lecturers than people who do different, you know, [other languages from around the world]. So, anyway, that’s where I come from.

Before the publishing house, I had a short experience in a production company in Canterbury as well. It was very small, we were only five people, but it was a production company focussed on the script, the scripted side of production, so we worked a lot with scriptwriters. And I felt like it wasn’t entirely my vocation. I enjoyed it and I thought that I could go down this path instead but, anyway, things didn’t work out - it’s a long story.

But it really helped me in seeing what a small company is, or can be, in the creative sector. My time there was really nice. I suppose it made it very approachable when you’re in an office with five other people and your boss is just another person like us, I suppose that gave me some kind of idea… It’s doable. You can do that. You can start something on your own.

That was at the end of the longest lockdown, I just realised that although I was working I wasn’t entirely happy. That’s a bit of a cliche but it’s true. I was reading one of the books by Rachel Cusk, Arlington Park, which is an old one and which is very special to me. It’s about five girlfriends, five women in their late thirties, they’re friends. It resonated with me a lot because I had a group of five best friends as well and the jobs that these women were doing in the book, I’d done almost all of them, and the places where they were living in London I’d lived in a couple of them as well. So it was very special. The main thing for me - and I don’t know if this is what Rachel intended when she was writing - I found that these women were at a stage in their lives where they were releasing that they’d all made bad choices at some point. And, because I was at a crossroads with what I was going to do next, I thought, ‘Well, I still haven’t regretted my choices’. I was thinking - professionally at this point, especially - ‘Just do it. Do something you really want to do!’

And so, for me, that moment was really defining. I had some savings at that point that had been sitting there forever and I thought, ‘You know what? Let's take the money and work in literature!’ And that’s how it all started.

JR: Do you think that your diving into publishing this way - coming straight from academia and production, having not worked up through the machine and seeing the systems and limitations in place already and the more traditional ways of publishing - has been a more freeing experience than if you had started at the bottom of the chain somewhere?

AMB: Yes, I actually have asked that myself. You might say, yes, but I also wonder if I’m missing some experience that would be valuable. Do you see what I mean?

I’ve never worked in publishing but what I have done which I haven’t mentioned is that while I was doing my PhD I operated with groups like the European Literature Network and I read manuscripts and things like that every now and then. So I had a good sense of the literature - especially literature which hasn’t yet been translated - and I knew where to start hunting for it.

And, I suppose, I went [in] without any preconceived ideas. I started looking for designers, I looked at the websites of publishers; most of them are very functional but I didn’t love any of the designs. Then I came across Laura [Kloos, GDLOOK] - she does absolutely everything, the covers, the website, everything - and I loved her designs. She’s never worked in publishing before but I just loved the designs she made for other companies, all kinds of companies, so I explained my idea - it was very important to translate the concept of the press into the visuals. We’re in a very visual world now. And she understood it very well and she told me, ‘Look, I’ve been looking at other publishers’ websites and I didn’t find any inspiration’ - so it was the same thing. So I just told her, ‘Do your thing’, because the logo worked very well and I’m just going to trust her instincts on that. I think the look of it is quite different to other publishing websites.

But also, as I say, I don’t know if that freeing thing is necessarily always a positive thing. I suppose I will always have this doubt of whether there is some kind of experience I didn’t have [going in]. But I think that this is maybe more for the technical things, but deep down I’m very confident when I choose a text and I don’t doubt this side of myself. But then when it comes to sales, for example, this is the hardest bit. Because in Sales and Marketing, you have lots of jobs that are just sales, sales, sales! This is one thing that I'm learning as I go.

JR: As an outsider, when you look at the world of publishing, say, you go into a bookshop and look down the shelves at all the spines and see all these ‘indie publishers’, like Granta, like Icon, like Canongate. But they’re huge in comparison, they have larger teams, and they have larger budgets, they have various departments working on big lists. But then you keep looking down the bookshelf and you see Bluemoose Books, And Other Stories, Fly On The Wall, Dead Ink, and they’re all small. Indie but different.

How have you found doing it all yourself and not necessarily having the support of a larger publishing team?

AMB: Well, I can’t hire anybody, James, I’m afraid. Yeah, to be honest. But I work with a lot of freelancers. To start with, it’s four books a year. This is quite doable. In the beginning, I remember the first one was very stressful because, well, it’s the first one so you’re worried about how the actual book is going look. You kind of have to trust a lot of people as well. I remember the timings were quite stressful, like, how long things were going to take, you know, to have the proofs ready, or whatever. Now, things have adjusted and I feel much more confident with the whole production chain.

Every book is a project. Every book has a lot of people working on it; someone like a translator, for example. Translators have been amazing, really. They are so grateful to be working on a book they like and they are really interested, in the book they translate, but also in the promotion and in helping you. They are very aware of the situation of the company. Very down-to-earth people. Most authors have also been really amazing and approachable and with some of them, you know, I have I would say not a friendship but we feel confident in texting each other for this or that. And then there’s editors and typesetting, etc. And everybody has been very supportive. So, there are periods of time when I’m busy, yes, there are also times when it’s not constant. Sometimes I have more space to breathe and it’s just doable, to be honest. Unless again, I’m missing something I should be doing!

But now, I try to do as much marketing as possible because we need to sell more books but also it is an issue with being in bookshops and sales representation. This is I would say the most difficult part of it.

JR: And that’s the main part most people outside of the industry don’t think about. They might not be aware of that link in the chain.

The part of the job that I loved the most when I was working in the bookshop was talking to reps and looking four, sometimes five, or six months ahead. That was one of the most enjoyable parts of the job, getting to peek behind the curtain slightly and that’s where the magic of the industry is, I think. People are still getting excited about books and waiting for these things to come out.

I was wondering if you have a similar kind of excitement with books when you’re working with such a massive lead time. Can you tell us what your submission process is like?

AMB: So, with submissions, a lot of agents send me books, sometimes also translators, occasionally authors - but I have only published Industrial Roots by Lisa Pike who is a Canadian author, who got in touch directly and I loved it, but for the rest I haven’t gone ahead with any of the author submissions.

I’m not super organised with that, to be honest. So, what I do is, I have a folder with submissions that I need to check. I only divide them by debuts and none. And then what I would do is start reading the first pages. Now, this is something that is very quick. So, if the first ten pages don’t really tell me anything, or I'm not convinced, I just pass. Also, I need to make sure I find four books that will really stay with me and in fact, I don’t have a list longer than that right now. Then, if I read the first pages and I like it I ask for more, that’s if it’s in English, the agent can send the whole thing. If it’s a translation of a language I read, let’s start there, I’d ask for a PDF and read it all. If I don’t read the language, I would ask whether they have a longer example or for more information on the author. If they’re the translator they’re usually very helpful.

JR: I think the submission process is very interesting. I think, like right now I’m looking at your website and you’ve got open submissions from authors but you’ve also got open submissions from translators, which is quite interesting.

But let's say you’re dealing with an agent, is that quite a collaborative process? Some of the agents I’ve spoken to might have already done a bit of editing before finding a home for them.

AMB: Yes, that would be if the manuscript is written in English, I think. For example, I am now talking with an agent for an English manuscript and I asked him if this has been edited a lot, what the writer is like, etc. And they had editors in-house, or freelance, for that one. But yes, I think when a manuscript is in English. They are more used to foreign authors pitching through agents, so then an agent will send a sample to you in English but the rest is up to you because if you go ahead with the book you will just need to rearrange everything and the agent isn’t really involved.

JR: So, from something being submitted to you, say you love it straight away, and then getting it onto a bookshelf, how long does that process usually take?

AMB: I think a year and a half, on average. Now, we start with two years but that’s because of the queue.

JR: Sure.

AMB: Yeah, so more or less that time. It’s not too long, I think.

JR: It’s not but it’s maybe longer than a lot of readers might be aware of. I think two years is quite a long time. You hear in the film world about pre-production and post-production, and that’s fairly well-known. You also hear a lot from authors, often about their first book taking years to write and then get published. I think the publishing process is more of a mystery.

AMB: There is one thing about that process that I think is quite key, which is the publicity time. Because when you have the proof copy, the advanced reading copy, the only thing left to do is proofread it. And that usually has been proofread as you go, but because we wait to get blurbs for the back covers and some journalists will only accept proofs about six months in advance of its publication; this is a long period and it’s kind of frozen, nothing is really being done. We’re just waiting for people to write about them, to send us a blurb. I think it’s a little misleading because of this waiting time, but the actual doing - translating, editing, typesetting, proofreading - it’s probably less than a year.

JR: In your experience, of reading multiple languages, and working with translators; do you have a preference as to whether you read them in English or in its original language?

AMB: Reading it in English is actually really important. It gives you the feel of it, a taste. I think, if I could I would just read it in English, but you won’t have the whole thing translated, you know, in the agency, so that’s why if I can I read the original just to know the whole book and then I can go ahead.

It’s very interesting because actually, not always, but translating a book from one language to another makes it change. It’s funny, you might have some books, for example, one of ours, Thirsty Sea [Erica Mou], I think it’s much better in English than in Italian. Just because of the style of the book, it’s very stream-of-consciousness, and I think the English language - which is more concise anyway - just allows for more, I don’t know - to me, it just sounds better.

JR: That’s interesting.

AMB: In other books, for example, in French, I think French is a long language, its sentences are long and, depending on the style of the book, you need to keep that. The translator needs to find a way to keep that. I think it is important to read the final product in English in that case.

JR: I would say, maybe in the last few years or so I’ve seen a trend towards this heightened love of translated fiction on the high street. More bookshops are stocking translated fiction, there’s more of an appetite for translated stories.

Do you have any idea why this might be? Have you seen this trend on your end?

AMB: James, my question really is, why hasn’t it always been like that?

Compared to Spain, for example, I don’t think that difference exists as much. I don’t know why here we talk so much about translated literature as opposed to English literature. It’s probably because I’m not from here originally, because I grew up in Spain where you knew, yeah, that was translated, but it’s not such a strong level. Do you see what I mean?

I genuinely can’t understand why it’s marketed in that way here. I’ve heard people argue that it’s got to be some kind of imperialistic mentality, but is it? I don’t know if that’s the reason, I don’t know where it started, but for me, the interesting question is, who first made that division? Was it the publishers? Was it the booksellers? Someone thought that if you tell a normal person on the street that a book has been translated they wouldn’t like it. Why? Why would that be?

But you work in a bookshop so maybe you have more of an idea!

JR: I know know, I think it is interesting. I mean, when we talk about ‘classics’ and when we talk about classic fiction I don’t think classic translated fiction is labelled in the same way.

AMB: Yeah, exactly.

JR: But then, classics are often put in a different part of the shop, you know, so still there’s that distinction, and I don’t know whether we are just a nation that likes things classified and separated. I don’t know if that’s the case.

At the bound, there were a few of us on the team who loved to read Japanese fiction. There’s a very specific style of writing. Aesthetically and tonally, there’s something very specific about Japanese translation. But then if you look at books by publishers like Tilted Axis Press, who’re promoting contemporary Asian literature, they all have a very different feel and we were finding a growing audience for those voices even in the North East.

As someone who doesn’t read multiple languages, what I’m interested in is what gets lost in translation. And the not knowing is part of the fascination. As someone who can read both, do you ever get to the point where, even once the translator’s handed it to you, you go, ‘Oh, it’s just not the same!’, or, ‘There’s something missing here’, and would you ever go back to them with corrections or suggestions?

AMB: Not because of that. My approach to that is that you really need to embrace the language, also the translation. So, what a text becomes in English… It’s really fun. I find it really cool to be able to work with different languages. You create a new text. It’s like writing a new world. The English language has its rules and its expressions, so as long as the meaning is kept, obviously, it’s like a new piece that stands by itself. I think there’s this thing we need to do which is jump in and embrace it and give away the original somehow. And I enjoy a lot reading the comments between the translator and the editor because that’s the stage where it’s the little details, it’s very interesting. I don’t think we should think about what gets lost in the translation.

JR: Ha! Ok, sure.

AMB: It’s a trap that stops you from enjoying it and embracing the new text, I think.

JR: I guess, there’s no way for me to know!

AMB: With Thirsty Sea, it was a very difficult text to translate, the author knew English and she was working with the translator, and I’m very happy that they are very good friends now, but that needed a lot of changing.

JR: It must be quite unique, to be so personal and hands-on with each book you put out. You can take the time to make sure those little things get ironed out.

Whereas I worry that in massive corporate publishing, the speed in which they need to churn some of these books out - because they’re dealing with so many - maybe there are these little things that slip through the net.

Do you think that working with four books a year is something you’re going to stick with in the future? If you see the press grow, would you still prefer to stay streamlined and focussed on those titles or do you think there’s a need for publishing to grow and this constant aim to be a ‘big’ publisher rather than enjoying the benefits of being a small independent?

AMB: Yeah, that’s a great question. I think I’ll need to see how I feel. I definitely think we’ll do more than four just because there are so many books I would like to publish. But it’s true that I haven’t thought about having a limit because of quality reasons.

Now, if that ever were to happen I would definitely prioritise quality. If I grow I’ll have other people working with me, probably, so maybe you can have more people doing four books each, for example. That could be doable, but definitely, I wouldn't want to rush things

JR: You’ve spoken about working with designers and how important that is. The books themselves are very striking and quite minimalist. Was that always something that you had in mind?

AMB: The minimalist aspect of the press, that I wanted from the beginning. But no, I talked to several designers and so, when I sensed that she, Laura, understood what I was saying, I said, ‘Shall we try the logo and see how it goes?’

She had never designed a book cover so we needed to see how that went. I gave her so many ideas and she came up with a few logos I think it was spot on, and she just just understood what I was telling her, really. She’s really awesome to work with. With the books, she doesn’t read them, I discuss it with the author, because authors love covers, and it’s important for them to feel that they have a beautiful book. So yes, the front cover is what concerns us and Laura actually does a few samples, one might be really abstract without any figurative kind of image, but by that time we already had the logo and the website so I think she knew more or less the kind of visuals we wanted, and then I just chose the first one and then we’ve stuck with that style ever since.

JR: And while we’re talking about covers, it’s also become more of a trend, and rightly so, I think, of having the translator’s name on the jacket. Why weren’t we always? It’s that weird? It’s such a collaborative act to get that book out into the world, why hide their name on the title pages three pages down, or something?

AMB: Ha! In a little font so no one can ever read it, great! Who reads the title page?

That’s again, for me, it’s my background. In Spain, I always see translators on the cover. I remember, when I started, there was this ‘translators on the cover’ movement, and I became a part of it without wanting or doing it on purpose. And then people started saying, ‘Oh, you’re into having the translators on the cover’, but that’s just natural for me, so I didn’t know there was this movement going on. But I suppose it is related to this classifying of books as translated or not translated. But it’s very funny, because in Spain, and I think now here as well, some translators are really famous. Some readers will choose their books based on the translators, sometimes. I hope that becomes the case here. I know, for example, Saskia Vogel, the translator of Days [Days & Days & Days, Tone Schunnesson], I know she’s quite well known in some sectors and I know some readers have read the book just because of her.

JR: It’s interesting though that they get that kind of, not just the recognition, but quite a following, too. And there are definitely translators that I will keep an eye out for. Maybe it is tonally, or the creative choices they might make that you might be able to pick up. Are you at a point where you might choose to work with a particular translator again, given the choice?

AMB: Well, yes, Saskia is doing another book for us now.

JR: How has that process been this time around?

AMB: So, there are two things here: next year I’m publishing an author again, so for the second time. I just think an author always needs the same translator unless something goes really wrong. Because I think the translators know the book so well, the insights they have - I’m always asking permission to use their notes in my marketing because they give their opinions of the books and think, ‘My God, that’s brilliant!’ So, they know the work and they appreciate how the author evolves, they have an already established relationship with the author while translating the first book, So I think that’s for me a must. So we have the same translator this time with the same author. The author, that’s also so important - they need to feel like their book is in good hands, and once they have established a relationship with the translator it gives them a lot of peace to know that it is in good hands. So there is also this aspect.

Then with Saskia, she’s translating another author now. In that case, Saskia really wanted to translate that author. With Tone Schunnesson, she was translated for the agency, but I know she likes her but she didn’t love it as much as she loves that one. That’s very important for me. If the translator really likes a book it’s going to work out nicely. And also in the case of Swedish language, there has been a bit of a crisis some years ago where they couldn’t find new good translators. The translators would be very old and couldn’t really connect to these new authors, so I know from an agent there was a bit of a thing there. And then Saskia has been one of the first very good new Swedish translators, together with a few others, and I really think she is one of the best.

JR: And that must be great for you, getting to work with such talent and such experience. You can rely on them as much as they need to rely on you to do the job.

AMB: Yeah, that’s very important. The relationship between the translator and author and between the publisher. And what you said before, when you work and when you focus so much on a project it becomes very personal, you can’t avoid people, it’s very one-to-one and if you’re doing well with someone you’re going to want to keep that person working with you.

JR: Absolutely!

And getting into the publishing world is one thing but actually being in it and having experienced it over the last few years, are there any other small presses that you see doing similar things, or a different thing entirely, but that you see doing really good work? Is there anyone that you look towards for inspiration?

AMB: An inspiration for me would be Peirene Press. I don’t know if you’re aware that their founder left. I met her, I knew her a little bit. She also writes so I’d interviewed her for one of her books. And I think Peirene Press was the first press that was so, like, the standard. One with a specific look, and specific guidelines, and a certain number of books a year. it was the first one I came across when I first moved to the UK. We didn’t really have this in Spain. I think, definitely, she was an inspiration for me. And now, of course, I have known many other presses but I still think Peirene was the most important one.

JR: And it’s certainly become quite fashionable to have that sort of design consistency throughout a range. Fitzcarraldo’s been doing that for a little while now but even And Other Stories this year has just had a revamp. And they’re all going for a very beautiful and quite minimalist but very uniform kind of design.

Have you thought of, maybe in the future, doing another run of books with a different designer?

AMB: For now, no. Because I think for some reason, the way the market is organised, it’s become very important to be identified and my sales rep will kill me if I change anything! But I have thought that if the company grows, is to do something different, like, for example, children’s books or something like that. In that case, they would need to be different. But yeah, for now, I don’t think that will happen.

JR: It seems to me like the response to the press has been very positive -

AMB: - has it? Thank you, James, I needed to hear that!

JR: Haha! Well, how do you feel the response has been since starting?

AMB: The key thing is, for me, I think bookshops are so important. I’ve learned that here in Canterbury believe it or not we don’t have any indie shops. So, there is only one Waterstones - there are two universities, but you have a small town, a small city. Anyway, I tried to always push my books there, and I know when they place the books on a table on the ground floor we sell all the copies. When they are on the shelf, it’s only if someone is looking for that book specifically. Booksellers are really, for me, they have all the power, to be honest with you. Because the books need to be found. Not everybody knows us on social media, most people don’t know us yet. So that has been the most difficult bit.

The feedback has been positive but I also wonder if the negative reviews I don’t receive are because if people don’t like it they don’t say anything! You never know the other side of the story. That keeps you in the dark and to me is the most difficult thing to navigate. I can see something that works but in general, I feel like I’m quite in the dark, especially when it comes to sales reps. I have gone to other small indie publishers and I feel everybody is in the same situation. No one really knows what’s going on with sales reps. Because they represent publishers but then they don’t read the books, most of the time. How do they talk to booksellers? Is it just a big mass email with lots of other books, or do they actually have a conversation? This is the toughest part.

My sales rep is obsessed with having reviews in the media. Now, we have Ultramarine [Mariette Navarro] in The TLS, in the Irish Times, and for sure I didn’t see any increase in sales in that period. There is also this change. How important are these old newspapers or are people more interested in social media? So, in general, I don’t really know what’s going on out there and that’s one of the most stressful parts of this. In terms of reception, I don’t know what booksellers think. I know my rep told me there was someone at Topping & Co. in Scotland, apparently, they find our covers too plain so they didn’t order any copies, for example. Now, other people, other booksellers love our covers, so… And is it all about the covers? I really don’t know!

JR: I guess, in a cutthroat world maybe the covers do really matter. I think it’s difficult because, going back to that relationship with your reps, I mean, we couldn’t function as a bookshop without really good reps. It’s something that you cultivate over a long time and I think they get to know your likes and dislikes, and also your buying habits, and little things like that make all the difference. I suppose there are smaller shops around the UK that won’t see reps, maybe they’re too remote, so they’re looking at catalogues or wholesaler charts, and it’ll be harder to find your audience that way.

But, for those who look at the playing field a bit more, look at what other bookshops are talking about; getting a good reputation for great events with great authors, and building those relationships that way is really important. I look at what other booksellers are pushing, and what are on their displays. They can really champion something and turn it into a bestseller.

AMB: It’s really difficult, James. I know some indies who have all the books, shops up in Scotland, lots of indies who also display our books. I know Ultramarine has been quite popular among booksellers, and you can tell. So yeah, I think it’s key.

JR: Let’s finish up looking into the future. What are you excited about coming out soon, is there anything that’s not been released yet that you can tell us about?

AMB: I think the last book we’re publishing this year, the translation by Saskia, again, it’s very interesting. So, it’s a Swedish book by Hanna Nordenhök and it’s called Caesaria. This is a gothic book, we are saving this for Halloween; it’s literary, it’s very literary, but it’s a gothic story. Hanna the author did a lot of research on American history and she came across in the archives this girl who existed called Caesaria, the main character of the novel, she was a baby born from C-section. At the time, it was in the nineteenth century when doctors were still trying to make that work so a lot of women died, and a lot of babies died too. But the book is the story of this girl who is born from C-section and the doctor who keeps her as a trophy in his mansion, and it’s about everything and all the people she sees. I don’t know if you’ve watched Poor Things. OK, so, very different, but the first part of the film when she is kept in the house, made me think a little bit about Caesaria. That book is coming out in North America as well at the same time, so we sold the North American rights to Bookhug Press in Canada. I’m hoping it goes well, this one is really very different.

AMB: So, I came to this country, I think, about thirteen years ago. I’m from Spain originally and I came to study literature, and that has been my passion forever, ever since I was very young. I came to do my Masters and I loved it and then went into my PhD and I loved it, and then I was a teaching at the uni here in Canterbury for two years.

Now, James, my passion in life was to become an academic and keep studying literature and I don’t know if you know how the landscape is at the moment, but it’s really terrible. They’re cancelling a lot of jobs in the Humanities and many of my lecturers were made redundant. It’s been really tragic. So, anyway, I couldn’t find a permanent position, not here or in any other university in this country for Literature - I did Comparative Literature. I basically focussed on literature in English, French and German. So, that, I think - well, now I’m jumping a little bit - there’s a lot of talk in this country about whether literature in translation is as popular as literature in English. The conclusion is no! For instance, not like it is in France or Spain where people read far more international authors, and I think that translates also in academia. Because, if you’re doing English there are far more jobs for English lecturers than people who do different, you know, [other languages from around the world]. So, anyway, that’s where I come from.

Before the publishing house, I had a short experience in a production company in Canterbury as well. It was very small, we were only five people, but it was a production company focussed on the script, the scripted side of production, so we worked a lot with scriptwriters. And I felt like it wasn’t entirely my vocation. I enjoyed it and I thought that I could go down this path instead but, anyway, things didn’t work out - it’s a long story.

But it really helped me in seeing what a small company is, or can be, in the creative sector. My time there was really nice. I suppose it made it very approachable when you’re in an office with five other people and your boss is just another person like us, I suppose that gave me some kind of idea… It’s doable. You can do that. You can start something on your own.

That was at the end of the longest lockdown, I just realised that although I was working I wasn’t entirely happy. That’s a bit of a cliche but it’s true. I was reading one of the books by Rachel Cusk, Arlington Park, which is an old one and which is very special to me. It’s about five girlfriends, five women in their late thirties, they’re friends. It resonated with me a lot because I had a group of five best friends as well and the jobs that these women were doing in the book, I’d done almost all of them, and the places where they were living in London I’d lived in a couple of them as well. So it was very special. The main thing for me - and I don’t know if this is what Rachel intended when she was writing - I found that these women were at a stage in their lives where they were releasing that they’d all made bad choices at some point. And, because I was at a crossroads with what I was going to do next, I thought, ‘Well, I still haven’t regretted my choices’. I was thinking - professionally at this point, especially - ‘Just do it. Do something you really want to do!’

And so, for me, that moment was really defining. I had some savings at that point that had been sitting there forever and I thought, ‘You know what? Let's take the money and work in literature!’ And that’s how it all started.

JR: Do you think that your diving into publishing this way - coming straight from academia and production, having not worked up through the machine and seeing the systems and limitations in place already and the more traditional ways of publishing - has been a more freeing experience than if you had started at the bottom of the chain somewhere?

AMB: Yes, I actually have asked that myself. You might say, yes, but I also wonder if I’m missing some experience that would be valuable. Do you see what I mean?

I’ve never worked in publishing but what I have done which I haven’t mentioned is that while I was doing my PhD I operated with groups like the European Literature Network and I read manuscripts and things like that every now and then. So I had a good sense of the literature - especially literature which hasn’t yet been translated - and I knew where to start hunting for it.

And, I suppose, I went [in] without any preconceived ideas. I started looking for designers, I looked at the websites of publishers; most of them are very functional but I didn’t love any of the designs. Then I came across Laura [Kloos, GDLOOK] - she does absolutely everything, the covers, the website, everything - and I loved her designs. She’s never worked in publishing before but I just loved the designs she made for other companies, all kinds of companies, so I explained my idea - it was very important to translate the concept of the press into the visuals. We’re in a very visual world now. And she understood it very well and she told me, ‘Look, I’ve been looking at other publishers’ websites and I didn’t find any inspiration’ - so it was the same thing. So I just told her, ‘Do your thing’, because the logo worked very well and I’m just going to trust her instincts on that. I think the look of it is quite different to other publishing websites.

But also, as I say, I don’t know if that freeing thing is necessarily always a positive thing. I suppose I will always have this doubt of whether there is some kind of experience I didn’t have [going in]. But I think that this is maybe more for the technical things, but deep down I’m very confident when I choose a text and I don’t doubt this side of myself. But then when it comes to sales, for example, this is the hardest bit. Because in Sales and Marketing, you have lots of jobs that are just sales, sales, sales! This is one thing that I'm learning as I go.

JR: As an outsider, when you look at the world of publishing, say, you go into a bookshop and look down the shelves at all the spines and see all these ‘indie publishers’, like Granta, like Icon, like Canongate. But they’re huge in comparison, they have larger teams, and they have larger budgets, they have various departments working on big lists. But then you keep looking down the bookshelf and you see Bluemoose Books, And Other Stories, Fly On The Wall, Dead Ink, and they’re all small. Indie but different.

How have you found doing it all yourself and not necessarily having the support of a larger publishing team?

AMB: Well, I can’t hire anybody, James, I’m afraid. Yeah, to be honest. But I work with a lot of freelancers. To start with, it’s four books a year. This is quite doable. In the beginning, I remember the first one was very stressful because, well, it’s the first one so you’re worried about how the actual book is going look. You kind of have to trust a lot of people as well. I remember the timings were quite stressful, like, how long things were going to take, you know, to have the proofs ready, or whatever. Now, things have adjusted and I feel much more confident with the whole production chain.

Every book is a project. Every book has a lot of people working on it; someone like a translator, for example. Translators have been amazing, really. They are so grateful to be working on a book they like and they are really interested, in the book they translate, but also in the promotion and in helping you. They are very aware of the situation of the company. Very down-to-earth people. Most authors have also been really amazing and approachable and with some of them, you know, I have I would say not a friendship but we feel confident in texting each other for this or that. And then there’s editors and typesetting, etc. And everybody has been very supportive. So, there are periods of time when I’m busy, yes, there are also times when it’s not constant. Sometimes I have more space to breathe and it’s just doable, to be honest. Unless again, I’m missing something I should be doing!

But now, I try to do as much marketing as possible because we need to sell more books but also it is an issue with being in bookshops and sales representation. This is I would say the most difficult part of it.

JR: And that’s the main part most people outside of the industry don’t think about. They might not be aware of that link in the chain.

The part of the job that I loved the most when I was working in the bookshop was talking to reps and looking four, sometimes five, or six months ahead. That was one of the most enjoyable parts of the job, getting to peek behind the curtain slightly and that’s where the magic of the industry is, I think. People are still getting excited about books and waiting for these things to come out.

I was wondering if you have a similar kind of excitement with books when you’re working with such a massive lead time. Can you tell us what your submission process is like?

AMB: So, with submissions, a lot of agents send me books, sometimes also translators, occasionally authors - but I have only published Industrial Roots by Lisa Pike who is a Canadian author, who got in touch directly and I loved it, but for the rest I haven’t gone ahead with any of the author submissions.

I’m not super organised with that, to be honest. So, what I do is, I have a folder with submissions that I need to check. I only divide them by debuts and none. And then what I would do is start reading the first pages. Now, this is something that is very quick. So, if the first ten pages don’t really tell me anything, or I'm not convinced, I just pass. Also, I need to make sure I find four books that will really stay with me and in fact, I don’t have a list longer than that right now. Then, if I read the first pages and I like it I ask for more, that’s if it’s in English, the agent can send the whole thing. If it’s a translation of a language I read, let’s start there, I’d ask for a PDF and read it all. If I don’t read the language, I would ask whether they have a longer example or for more information on the author. If they’re the translator they’re usually very helpful.

JR: I think the submission process is very interesting. I think, like right now I’m looking at your website and you’ve got open submissions from authors but you’ve also got open submissions from translators, which is quite interesting.

But let's say you’re dealing with an agent, is that quite a collaborative process? Some of the agents I’ve spoken to might have already done a bit of editing before finding a home for them.

AMB: Yes, that would be if the manuscript is written in English, I think. For example, I am now talking with an agent for an English manuscript and I asked him if this has been edited a lot, what the writer is like, etc. And they had editors in-house, or freelance, for that one. But yes, I think when a manuscript is in English. They are more used to foreign authors pitching through agents, so then an agent will send a sample to you in English but the rest is up to you because if you go ahead with the book you will just need to rearrange everything and the agent isn’t really involved.

JR: So, from something being submitted to you, say you love it straight away, and then getting it onto a bookshelf, how long does that process usually take?

AMB: I think a year and a half, on average. Now, we start with two years but that’s because of the queue.

JR: Sure.

AMB: Yeah, so more or less that time. It’s not too long, I think.

JR: It’s not but it’s maybe longer than a lot of readers might be aware of. I think two years is quite a long time. You hear in the film world about pre-production and post-production, and that’s fairly well-known. You also hear a lot from authors, often about their first book taking years to write and then get published. I think the publishing process is more of a mystery.

AMB: There is one thing about that process that I think is quite key, which is the publicity time. Because when you have the proof copy, the advanced reading copy, the only thing left to do is proofread it. And that usually has been proofread as you go, but because we wait to get blurbs for the back covers and some journalists will only accept proofs about six months in advance of its publication; this is a long period and it’s kind of frozen, nothing is really being done. We’re just waiting for people to write about them, to send us a blurb. I think it’s a little misleading because of this waiting time, but the actual doing - translating, editing, typesetting, proofreading - it’s probably less than a year.

JR: In your experience, of reading multiple languages, and working with translators; do you have a preference as to whether you read them in English or in its original language?

AMB: Reading it in English is actually really important. It gives you the feel of it, a taste. I think, if I could I would just read it in English, but you won’t have the whole thing translated, you know, in the agency, so that’s why if I can I read the original just to know the whole book and then I can go ahead.

It’s very interesting because actually, not always, but translating a book from one language to another makes it change. It’s funny, you might have some books, for example, one of ours, Thirsty Sea [Erica Mou], I think it’s much better in English than in Italian. Just because of the style of the book, it’s very stream-of-consciousness, and I think the English language - which is more concise anyway - just allows for more, I don’t know - to me, it just sounds better.

JR: That’s interesting.

AMB: In other books, for example, in French, I think French is a long language, its sentences are long and, depending on the style of the book, you need to keep that. The translator needs to find a way to keep that. I think it is important to read the final product in English in that case.

JR: I would say, maybe in the last few years or so I’ve seen a trend towards this heightened love of translated fiction on the high street. More bookshops are stocking translated fiction, there’s more of an appetite for translated stories.

Do you have any idea why this might be? Have you seen this trend on your end?

AMB: James, my question really is, why hasn’t it always been like that?

Compared to Spain, for example, I don’t think that difference exists as much. I don’t know why here we talk so much about translated literature as opposed to English literature. It’s probably because I’m not from here originally, because I grew up in Spain where you knew, yeah, that was translated, but it’s not such a strong level. Do you see what I mean?

I genuinely can’t understand why it’s marketed in that way here. I’ve heard people argue that it’s got to be some kind of imperialistic mentality, but is it? I don’t know if that’s the reason, I don’t know where it started, but for me, the interesting question is, who first made that division? Was it the publishers? Was it the booksellers? Someone thought that if you tell a normal person on the street that a book has been translated they wouldn’t like it. Why? Why would that be?

But you work in a bookshop so maybe you have more of an idea!

JR: I know know, I think it is interesting. I mean, when we talk about ‘classics’ and when we talk about classic fiction I don’t think classic translated fiction is labelled in the same way.

AMB: Yeah, exactly.

JR: But then, classics are often put in a different part of the shop, you know, so still there’s that distinction, and I don’t know whether we are just a nation that likes things classified and separated. I don’t know if that’s the case.

At the bound, there were a few of us on the team who loved to read Japanese fiction. There’s a very specific style of writing. Aesthetically and tonally, there’s something very specific about Japanese translation. But then if you look at books by publishers like Tilted Axis Press, who’re promoting contemporary Asian literature, they all have a very different feel and we were finding a growing audience for those voices even in the North East.

As someone who doesn’t read multiple languages, what I’m interested in is what gets lost in translation. And the not knowing is part of the fascination. As someone who can read both, do you ever get to the point where, even once the translator’s handed it to you, you go, ‘Oh, it’s just not the same!’, or, ‘There’s something missing here’, and would you ever go back to them with corrections or suggestions?

AMB: Not because of that. My approach to that is that you really need to embrace the language, also the translation. So, what a text becomes in English… It’s really fun. I find it really cool to be able to work with different languages. You create a new text. It’s like writing a new world. The English language has its rules and its expressions, so as long as the meaning is kept, obviously, it’s like a new piece that stands by itself. I think there’s this thing we need to do which is jump in and embrace it and give away the original somehow. And I enjoy a lot reading the comments between the translator and the editor because that’s the stage where it’s the little details, it’s very interesting. I don’t think we should think about what gets lost in the translation.

JR: Ha! Ok, sure.

AMB: It’s a trap that stops you from enjoying it and embracing the new text, I think.

JR: I guess, there’s no way for me to know!

AMB: With Thirsty Sea, it was a very difficult text to translate, the author knew English and she was working with the translator, and I’m very happy that they are very good friends now, but that needed a lot of changing.

JR: It must be quite unique, to be so personal and hands-on with each book you put out. You can take the time to make sure those little things get ironed out.

Whereas I worry that in massive corporate publishing, the speed in which they need to churn some of these books out - because they’re dealing with so many - maybe there are these little things that slip through the net.

Do you think that working with four books a year is something you’re going to stick with in the future? If you see the press grow, would you still prefer to stay streamlined and focussed on those titles or do you think there’s a need for publishing to grow and this constant aim to be a ‘big’ publisher rather than enjoying the benefits of being a small independent?

AMB: Yeah, that’s a great question. I think I’ll need to see how I feel. I definitely think we’ll do more than four just because there are so many books I would like to publish. But it’s true that I haven’t thought about having a limit because of quality reasons.

Now, if that ever were to happen I would definitely prioritise quality. If I grow I’ll have other people working with me, probably, so maybe you can have more people doing four books each, for example. That could be doable, but definitely, I wouldn't want to rush things

JR: You’ve spoken about working with designers and how important that is. The books themselves are very striking and quite minimalist. Was that always something that you had in mind?

AMB: The minimalist aspect of the press, that I wanted from the beginning. But no, I talked to several designers and so, when I sensed that she, Laura, understood what I was saying, I said, ‘Shall we try the logo and see how it goes?’

She had never designed a book cover so we needed to see how that went. I gave her so many ideas and she came up with a few logos I think it was spot on, and she just just understood what I was telling her, really. She’s really awesome to work with. With the books, she doesn’t read them, I discuss it with the author, because authors love covers, and it’s important for them to feel that they have a beautiful book. So yes, the front cover is what concerns us and Laura actually does a few samples, one might be really abstract without any figurative kind of image, but by that time we already had the logo and the website so I think she knew more or less the kind of visuals we wanted, and then I just chose the first one and then we’ve stuck with that style ever since.

JR: And while we’re talking about covers, it’s also become more of a trend, and rightly so, I think, of having the translator’s name on the jacket. Why weren’t we always? It’s that weird? It’s such a collaborative act to get that book out into the world, why hide their name on the title pages three pages down, or something?

AMB: Ha! In a little font so no one can ever read it, great! Who reads the title page?

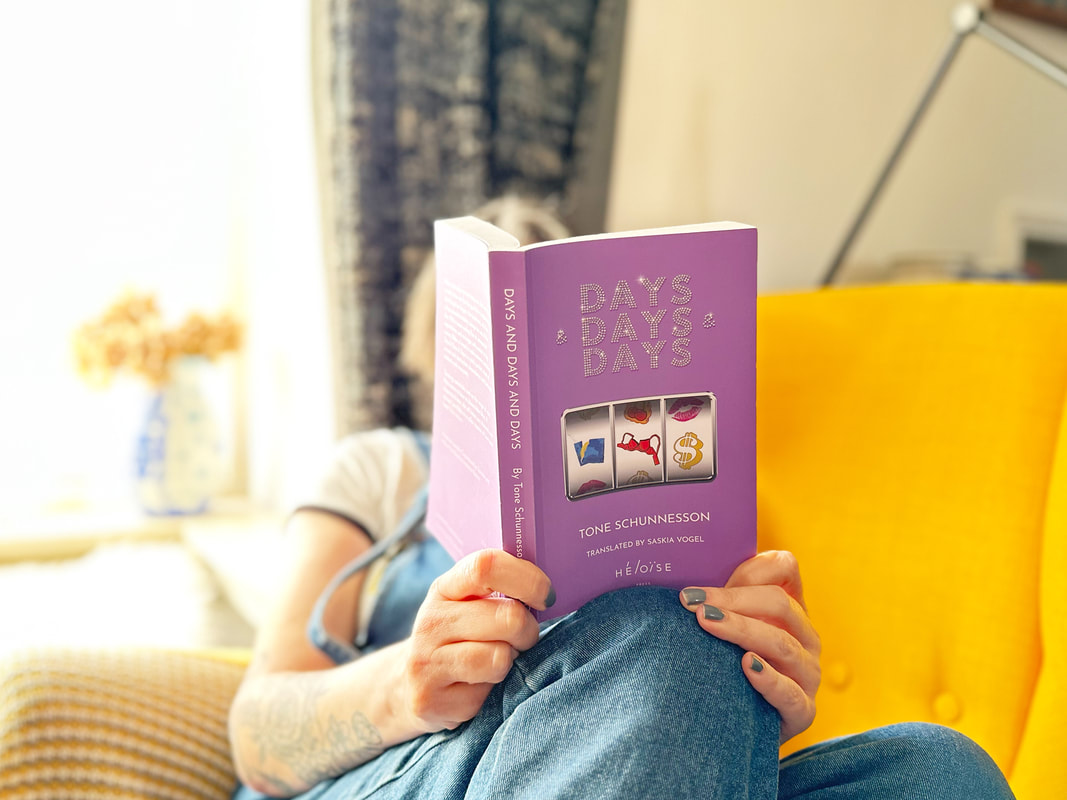

That’s again, for me, it’s my background. In Spain, I always see translators on the cover. I remember, when I started, there was this ‘translators on the cover’ movement, and I became a part of it without wanting or doing it on purpose. And then people started saying, ‘Oh, you’re into having the translators on the cover’, but that’s just natural for me, so I didn’t know there was this movement going on. But I suppose it is related to this classifying of books as translated or not translated. But it’s very funny, because in Spain, and I think now here as well, some translators are really famous. Some readers will choose their books based on the translators, sometimes. I hope that becomes the case here. I know, for example, Saskia Vogel, the translator of Days [Days & Days & Days, Tone Schunnesson], I know she’s quite well known in some sectors and I know some readers have read the book just because of her.

JR: It’s interesting though that they get that kind of, not just the recognition, but quite a following, too. And there are definitely translators that I will keep an eye out for. Maybe it is tonally, or the creative choices they might make that you might be able to pick up. Are you at a point where you might choose to work with a particular translator again, given the choice?

AMB: Well, yes, Saskia is doing another book for us now.

JR: How has that process been this time around?

AMB: So, there are two things here: next year I’m publishing an author again, so for the second time. I just think an author always needs the same translator unless something goes really wrong. Because I think the translators know the book so well, the insights they have - I’m always asking permission to use their notes in my marketing because they give their opinions of the books and think, ‘My God, that’s brilliant!’ So, they know the work and they appreciate how the author evolves, they have an already established relationship with the author while translating the first book, So I think that’s for me a must. So we have the same translator this time with the same author. The author, that’s also so important - they need to feel like their book is in good hands, and once they have established a relationship with the translator it gives them a lot of peace to know that it is in good hands. So there is also this aspect.

Then with Saskia, she’s translating another author now. In that case, Saskia really wanted to translate that author. With Tone Schunnesson, she was translated for the agency, but I know she likes her but she didn’t love it as much as she loves that one. That’s very important for me. If the translator really likes a book it’s going to work out nicely. And also in the case of Swedish language, there has been a bit of a crisis some years ago where they couldn’t find new good translators. The translators would be very old and couldn’t really connect to these new authors, so I know from an agent there was a bit of a thing there. And then Saskia has been one of the first very good new Swedish translators, together with a few others, and I really think she is one of the best.

JR: And that must be great for you, getting to work with such talent and such experience. You can rely on them as much as they need to rely on you to do the job.

AMB: Yeah, that’s very important. The relationship between the translator and author and between the publisher. And what you said before, when you work and when you focus so much on a project it becomes very personal, you can’t avoid people, it’s very one-to-one and if you’re doing well with someone you’re going to want to keep that person working with you.

JR: Absolutely!

And getting into the publishing world is one thing but actually being in it and having experienced it over the last few years, are there any other small presses that you see doing similar things, or a different thing entirely, but that you see doing really good work? Is there anyone that you look towards for inspiration?

AMB: An inspiration for me would be Peirene Press. I don’t know if you’re aware that their founder left. I met her, I knew her a little bit. She also writes so I’d interviewed her for one of her books. And I think Peirene Press was the first press that was so, like, the standard. One with a specific look, and specific guidelines, and a certain number of books a year. it was the first one I came across when I first moved to the UK. We didn’t really have this in Spain. I think, definitely, she was an inspiration for me. And now, of course, I have known many other presses but I still think Peirene was the most important one.

JR: And it’s certainly become quite fashionable to have that sort of design consistency throughout a range. Fitzcarraldo’s been doing that for a little while now but even And Other Stories this year has just had a revamp. And they’re all going for a very beautiful and quite minimalist but very uniform kind of design.

Have you thought of, maybe in the future, doing another run of books with a different designer?

AMB: For now, no. Because I think for some reason, the way the market is organised, it’s become very important to be identified and my sales rep will kill me if I change anything! But I have thought that if the company grows, is to do something different, like, for example, children’s books or something like that. In that case, they would need to be different. But yeah, for now, I don’t think that will happen.

JR: It seems to me like the response to the press has been very positive -

AMB: - has it? Thank you, James, I needed to hear that!

JR: Haha! Well, how do you feel the response has been since starting?

AMB: The key thing is, for me, I think bookshops are so important. I’ve learned that here in Canterbury believe it or not we don’t have any indie shops. So, there is only one Waterstones - there are two universities, but you have a small town, a small city. Anyway, I tried to always push my books there, and I know when they place the books on a table on the ground floor we sell all the copies. When they are on the shelf, it’s only if someone is looking for that book specifically. Booksellers are really, for me, they have all the power, to be honest with you. Because the books need to be found. Not everybody knows us on social media, most people don’t know us yet. So that has been the most difficult bit.

The feedback has been positive but I also wonder if the negative reviews I don’t receive are because if people don’t like it they don’t say anything! You never know the other side of the story. That keeps you in the dark and to me is the most difficult thing to navigate. I can see something that works but in general, I feel like I’m quite in the dark, especially when it comes to sales reps. I have gone to other small indie publishers and I feel everybody is in the same situation. No one really knows what’s going on with sales reps. Because they represent publishers but then they don’t read the books, most of the time. How do they talk to booksellers? Is it just a big mass email with lots of other books, or do they actually have a conversation? This is the toughest part.

My sales rep is obsessed with having reviews in the media. Now, we have Ultramarine [Mariette Navarro] in The TLS, in the Irish Times, and for sure I didn’t see any increase in sales in that period. There is also this change. How important are these old newspapers or are people more interested in social media? So, in general, I don’t really know what’s going on out there and that’s one of the most stressful parts of this. In terms of reception, I don’t know what booksellers think. I know my rep told me there was someone at Topping & Co. in Scotland, apparently, they find our covers too plain so they didn’t order any copies, for example. Now, other people, other booksellers love our covers, so… And is it all about the covers? I really don’t know!

JR: I guess, in a cutthroat world maybe the covers do really matter. I think it’s difficult because, going back to that relationship with your reps, I mean, we couldn’t function as a bookshop without really good reps. It’s something that you cultivate over a long time and I think they get to know your likes and dislikes, and also your buying habits, and little things like that make all the difference. I suppose there are smaller shops around the UK that won’t see reps, maybe they’re too remote, so they’re looking at catalogues or wholesaler charts, and it’ll be harder to find your audience that way.

But, for those who look at the playing field a bit more, look at what other bookshops are talking about; getting a good reputation for great events with great authors, and building those relationships that way is really important. I look at what other booksellers are pushing, and what are on their displays. They can really champion something and turn it into a bestseller.

AMB: It’s really difficult, James. I know some indies who have all the books, shops up in Scotland, lots of indies who also display our books. I know Ultramarine has been quite popular among booksellers, and you can tell. So yeah, I think it’s key.

JR: Let’s finish up looking into the future. What are you excited about coming out soon, is there anything that’s not been released yet that you can tell us about?

AMB: I think the last book we’re publishing this year, the translation by Saskia, again, it’s very interesting. So, it’s a Swedish book by Hanna Nordenhök and it’s called Caesaria. This is a gothic book, we are saving this for Halloween; it’s literary, it’s very literary, but it’s a gothic story. Hanna the author did a lot of research on American history and she came across in the archives this girl who existed called Caesaria, the main character of the novel, she was a baby born from C-section. At the time, it was in the nineteenth century when doctors were still trying to make that work so a lot of women died, and a lot of babies died too. But the book is the story of this girl who is born from C-section and the doctor who keeps her as a trophy in his mansion, and it’s about everything and all the people she sees. I don’t know if you’ve watched Poor Things. OK, so, very different, but the first part of the film when she is kept in the house, made me think a little bit about Caesaria. That book is coming out in North America as well at the same time, so we sold the North American rights to Bookhug Press in Canada. I’m hoping it goes well, this one is really very different.

|

Go and show some support for Aina and Héloïse Press by browsing their website and taking a look at what exciting new titles they have coming this year. Plus, check out their Events and Subscription offers to experience the best new fiction and live author talks that Héloïse Press has to offer across the UK.

|